The meeting ends, everyone files out, and there it is again, that familiar knot in my stomach. Did I miss something important? Did I talk too much? Did I even come across the way I meant to? For years, that quiet second-guessing followed me out of conversations.

For many neurodivergent people, that's not a small inconvenience. It's a constant weight. The world of work, education, and even casual interactions is often built around a communication style that assumes everyone can track, retain, and respond in "real time". But the reality is, plenty of us can't. Not without cost.

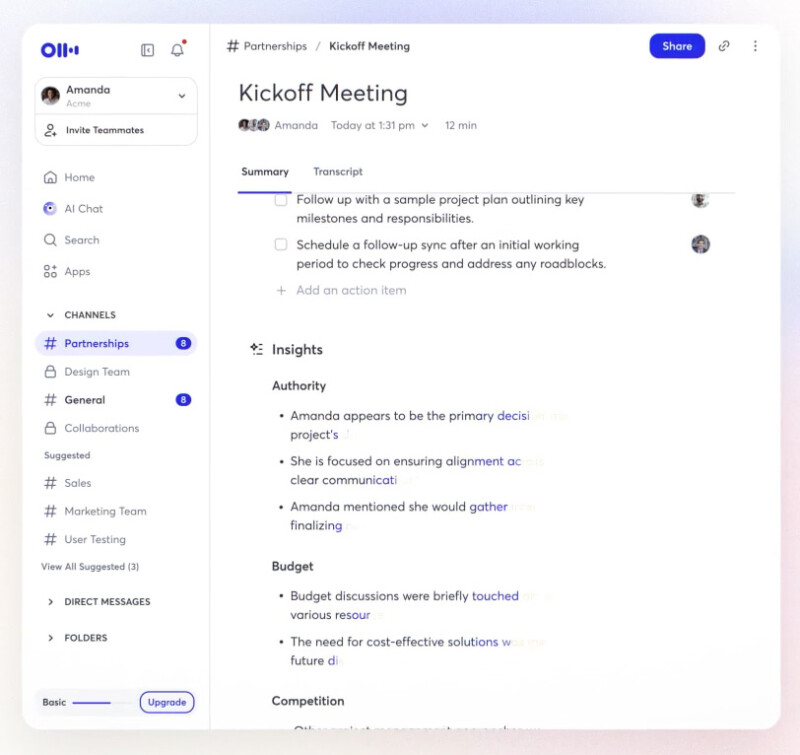

Then AI tools arrived. Live transcription services like Otter.ai, Grammarly's email tone analysers, meeting summarisers built into Zoom, Google Meet and Teams, even chatbot-based social coaching platforms. Suddenly, there was a new layer of accessibility that did not just help us keep up. It helped us show up.

So the question I've been wrestling with is this: Is AI the single biggest accessibility gain neurodiverse people have ever had? To answer that, we need to understand what makes an accessibility breakthrough truly transformative, and whether AI's current promises hold up against both its potential and its problems.

Why Meetings Can be a Challenge for Neurodiverse People

Meetings can feel like marathons run with untied shoelaces, but the experience varies dramatically across the neurodivergent spectrum. For someone with ADHD, the challenge might be maintaining focus while simultaneously processing rapid-fire information and taking notes. For someone on the autism spectrum, it could be decoding implied meanings and social cues while managing sensory overload from fluorescent lights or competing voices. For those with auditory processing differences, it is the exhausting work of translating sounds into meaning in real time.

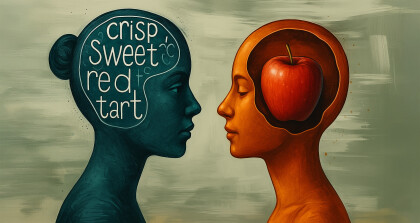

I remember reading about Kate D'hotman, a filmmaker with both autism and ADHD, who described how sending suggestions to her manager used to feel like "sending bombs". She would write a bulleted list of improvements; what she meant as helpful feedback came across as "overly blunt", even rude. With AI tools like ChatGPT, she now runs ideas through a filter: "Does this feel too harsh? Too direct?" That kind of mirror has fundamentally changed her professional relationships.

But Kate's experience raises an immediate question: what happens to people who cannot afford premium AI subscriptions, or whose workplaces have not adopted these tools? The accessibility gains she describes are not equally distributed, and that disparity matters when we are evaluating the technology's broader impact.

Beyond Communication: The Broader Neurodivergent Experience with AI Tools

While communication challenges get much of the attention in discussions about AI and neurodiversity, they are just one piece of a complex puzzle. Executive function, the mental processes that include working memory, flexible thinking, and self-control, often work differently for neurodivergent people. These differences create challenges that extend far beyond meetings and emails.

A recent study by EY involving over 300 neurodivergent employees found that 85% believe AI workplace tools like Microsoft 365 Copilot can create more inclusive environments, with 91% viewing such tools as valuable assistive technology. However, the research also highlighted significant variation in how people respond. While many found AI helpful for tasks like email drafting and meeting summarisation, responses differed by individual need, workplace context, and specific type of neurodivergence.

This is why AI’s impact feels uneven. In some contexts, it opens doors, providing external structure that helps people work and communicate on their own terms. In others, it simply reminds us how many barriers remain, such as sensory overload in open offices or the visual strain of screen-based systems. For every person who gains freedom, another may find the technology misses their reality entirely.

What Makes an Accessibility Breakthrough "Biggest"?

So, what makes a breakthrough truly transformative? The biggest ones are usually easy to adopt, remove deep barriers rather than surface problems, create knock-on benefits across different areas of life, and eventually change not just individual experience but wider social expectations.

Closed captioning, for example, not only helped deaf and hard-of-hearing people, it also changed how we approach information access in noisy places, language learning, and even attention management. The curb cut effect, where accessibility improvements benefit everyone, has made captions nearly universal on video content.

Screen readers transformed not only access to digital information but also pushed entire industries towards accessible web design standards. Predictive text, once seen as a novelty, became essential for people with dyslexia and motor challenges, and then quietly reshaped how everyone writes and communicates.

So how does AI stack up against these examples? It looks promising, especially as it is already being built into everyday tools from smartphones to workplace platforms. The real question is whether it truly tackles the deeper barriers or just offers short-term workarounds, and whether its benefits will grow over time or create new dependencies.

The AI Accessibility Landscape: What’s Working, What’s Not

AI tools right now are a bit of a mixed bag. Live transcription has improved a lot, with some systems hitting over 95% accuracy in clear conditions with little background noise. But those figures depend on “ideal” conditions. Accuracy drops quickly with strong accents, overlapping voices, or technical jargon, and it can fall even further in noisy group settings.

Tone checkers in email and messaging apps, like Grammarly or Outlook, can help ease the kind of communication worries many people face. But they are not perfect. Early users have pointed out some big cultural blind spots. For example, something that sounds perfectly fine in Dutch business culture might get flagged as “too harsh” by an AI trained mostly on American English.

Task management tools look especially promising. Apps like Motion use AI to plan your day around energy levels and focus patterns, while tools like Clockify track time and spot productivity trends without you needing to log everything yourself. For people with ADHD, this kind of external structure can make a real difference where traditional planners often fall short.

Not every tool delivers, though. Social skills training apps that use AI to simulate conversations often feel stiff and unnatural, missing the nuance of real human interaction. Some people even say practising with them increased their anxiety about social situations, because the almost-but-not-quite-human responses felt more unsettling than helpful.

Are AI Accessibility Tools Creating New Dependencies?

One of the trickier issues with AI accessibility tools is dependency. Traditional assistive tech usually supports existing abilities, like screen readers helping people access visual information. AI, on the other hand, can sometimes feel like it is doing the whole job for you, such as drafting, revising, and even sending emails.

Alice Bennett from the University of York's Digital Accessibility Unit warns that while these tools can help, "real accessibility requires engagement". The risk is that if we lean too heavily on AI, we create the illusion of inclusivity rather than the real thing.

But for people like Kate D’hotman, AI is simply empowering. She says, "I'm not dependent on ChatGPT any more than someone who wears glasses is dependent on them. It's a tool that lets me show up as my best self." Without it, she explains, too much energy goes into second-guessing and not enough into the creative work that plays to her strengths.

The truth probably sits somewhere in the middle, and it will differ for each person. What we need now is more long-term research on how sustained AI use shapes skills, confidence, and independence for neurodivergent people.

Building Inclusive AI: Designing for Neurodiversity and Accessibility

To ensure AI serves neurodivergent communities effectively, we need true co-creation with neurodivergent people involved from the earliest design stages, not just as testers. As Meier Galblum Haigh put it in a Mozilla Foundation interview, "My big magical fix would be putting the folks most impacted by AI in charge of regulating and visioning it. At this moment, the best way we can achieve that is by organizing, as I do not think governments or Big Tech companies will just hand us their power!".

Accessibility must also include affordability. The most sophisticated AI tools should not be luxury items available only to those with premium workplace benefits. Finally, we need to maintain space for authentic neurodivergent voices without constant translation or smoothing.

So, Is AI the Biggest Accessibility Gain Ever?

In terms of breadth and adoption speed, AI is unprecedented. It touches communication, memory, social interaction, and task management simultaneously, while being built into mainstream platforms at commercial speed rather than requiring decades of advocacy.

But for the depth of long-term impact, it is too early to tell. We do not yet know whether AI tools will prove to be reliable assistive technologies people use for decades, or whether they will require constant evolution to remain useful.

What I can say is this. For the first time in my professional life, I leave meetings confident that I caught the important details. I send emails without spending hours overthinking them. I have cognitive bandwidth left for the creative work that I enjoy the most. That familiar knot in my stomach is still there sometimes, but now I have tools to untangle it. That is more than convenience. That is accessibility.

The question is not just whether AI represents the biggest accessibility gain ever. It is whether we can shape its development so that those gains are distributed equitably and preserve space for neurodivergent perspectives. The technology is powerful enough that we have a responsibility to get this right.